(Many thanks, again, to Sharon Rogers for sharing this article!)

The research paves the way for brain implants that would translate the thoughts of people who have lost power of speech.

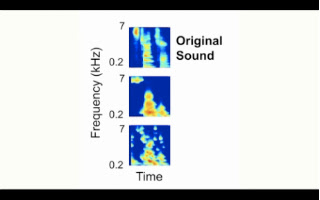

Algorithms translated the brain activity associated with hearing

'Waldo', 'structure', 'doubt' and 'property' into recognisable words. LINK to Video: PLoS Biology

Scientists have picked up fragments of people's thoughts by decoding the brain activity caused by words that they hear. The remarkable feat has given researchers fresh insight into how the brain processes language, and raises the tantalising prospect of devices that can return speech to the speechless. Though

in its infancy, the work paves the way for brain implants that could

monitor a person's thoughts and speak words and sentences as they

imagine them. Such devices could transform the lives of thousands

of people who lose the ability to speak as a result of a stroke or other

medical conditions.

Experiments on 15 patients in the US showed that a computer could decipher their brain activity and play back words they heard, though at times the words were difficult to recognise. "This is exciting in terms of the basic science of how the brain decodes what we hear," said Robert Knight, a senior member of the team and director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at the University of California, Berkeley.

"Potentially, the technique could be used to develop an implantable prosthetic device to aid speaking, and for some patients that would be wonderful. The next step is to test whether we can decode a word when a person imagines it. That might sound spooky, but this could really help patients. Perhaps in 10 years it will be as common as grandmother getting a new hip," Knight said. The study is published in the journal PLoS Biology.

The scientists ran tests on patients who were already in hospital for an operation to treat intractable epilepsy. In that procedure, patients have the top of their skull removed and a net of electrodes laid across the surface of their brain. Doctors use the electrodes to identify the precise trigger point of the patient's fit, before removing the tissue. Sometimes, patients wait for days before they have enough seizures to locate the source of the problem.

Scientist Brian Pasley enrolled 15 patients to take part. He played each a series of words for five to 10 minutes while recording their brain activity from the electrode nets. He then created computer programs that could recognise sounds encoded in the brain waves.

The brain seems to break sounds down into their constituent acoustic frequencies. The most important range for speech is 1-8,000 Hertz. Pasley compared the technique to a pianist who can hear a piece in their mind just by knowing which keys are played. He next played a collection of new words to the patients to see if the algorithms could pick out and repeat recognisable words. Among them were words such as "Waldo", "structure", "doubt" and "property".

The scientists got their best results when they recorded activity in the superior temporal gyrus, part of the brain that sits to one side, above the ear. "I didn't think it could possibly work, but Brian did it," said Knight. "His model can reproduce the sound the patient heard and you can actually recognise the word, though not at a perfect level."

The prospect of reading minds has led to ethical concerns that the technology could be used covertly or to interrogate criminals and terrorists. Knight said that is in the realm of science fiction. "To reproduce what we did, you would have to open up someone's skull and they would have to co-operate." Making a device to help people speak will not be easy. Brain signals that encode imagined words could be harder to decipher and the device must be small and operate wirelessly. Another potential headache is distinguishing between words a person wants to say and thoughts they would rather keep private.

Jan Schnupp, professor of neuroscience at Oxford University called the work "remarkable".

"Neuroscientists have long believed that the brain works by translating aspects of the external world, such as spoken words, into patterns of electrical activity. But proving that this is true by showing that it is possible to translate these activity patterns back into the original sound – or at least a fair approximation – is nevertheless a great step forward. It paves the way to rapid progress toward biomedical applications," he said.

"Some may worry though that this sort of technology might lead to mind-reading devices which could one day be used to eavesdrop on the privacy of our thoughts. Such worries are unjustified. It is worth remembering that these scientists could only get their technique to work because epileptic patients had cooperated closely and willingly with them, and allowed a large array of electrodes to be placed directly on the surface of their brains.

"We can rest assured that our skulls will remain an impenetrable barrier for any would-be technological mind hacker for any foreseeable future," he added.

Experiments on 15 patients in the US showed that a computer could decipher their brain activity and play back words they heard, though at times the words were difficult to recognise. "This is exciting in terms of the basic science of how the brain decodes what we hear," said Robert Knight, a senior member of the team and director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at the University of California, Berkeley.

"Potentially, the technique could be used to develop an implantable prosthetic device to aid speaking, and for some patients that would be wonderful. The next step is to test whether we can decode a word when a person imagines it. That might sound spooky, but this could really help patients. Perhaps in 10 years it will be as common as grandmother getting a new hip," Knight said. The study is published in the journal PLoS Biology.

The scientists ran tests on patients who were already in hospital for an operation to treat intractable epilepsy. In that procedure, patients have the top of their skull removed and a net of electrodes laid across the surface of their brain. Doctors use the electrodes to identify the precise trigger point of the patient's fit, before removing the tissue. Sometimes, patients wait for days before they have enough seizures to locate the source of the problem.

Scientist Brian Pasley enrolled 15 patients to take part. He played each a series of words for five to 10 minutes while recording their brain activity from the electrode nets. He then created computer programs that could recognise sounds encoded in the brain waves.

The brain seems to break sounds down into their constituent acoustic frequencies. The most important range for speech is 1-8,000 Hertz. Pasley compared the technique to a pianist who can hear a piece in their mind just by knowing which keys are played. He next played a collection of new words to the patients to see if the algorithms could pick out and repeat recognisable words. Among them were words such as "Waldo", "structure", "doubt" and "property".

The scientists got their best results when they recorded activity in the superior temporal gyrus, part of the brain that sits to one side, above the ear. "I didn't think it could possibly work, but Brian did it," said Knight. "His model can reproduce the sound the patient heard and you can actually recognise the word, though not at a perfect level."

The prospect of reading minds has led to ethical concerns that the technology could be used covertly or to interrogate criminals and terrorists. Knight said that is in the realm of science fiction. "To reproduce what we did, you would have to open up someone's skull and they would have to co-operate." Making a device to help people speak will not be easy. Brain signals that encode imagined words could be harder to decipher and the device must be small and operate wirelessly. Another potential headache is distinguishing between words a person wants to say and thoughts they would rather keep private.

Jan Schnupp, professor of neuroscience at Oxford University called the work "remarkable".

"Neuroscientists have long believed that the brain works by translating aspects of the external world, such as spoken words, into patterns of electrical activity. But proving that this is true by showing that it is possible to translate these activity patterns back into the original sound – or at least a fair approximation – is nevertheless a great step forward. It paves the way to rapid progress toward biomedical applications," he said.

"Some may worry though that this sort of technology might lead to mind-reading devices which could one day be used to eavesdrop on the privacy of our thoughts. Such worries are unjustified. It is worth remembering that these scientists could only get their technique to work because epileptic patients had cooperated closely and willingly with them, and allowed a large array of electrodes to be placed directly on the surface of their brains.

"We can rest assured that our skulls will remain an impenetrable barrier for any would-be technological mind hacker for any foreseeable future," he added.

No comments:

Post a Comment